Liam Cassidy, The University of Melbourne; Andrew King, The University of Melbourne; Josephine Brown, The University of Melbourne, and Tilo Ziehn, CSIRO

Humanity’s emissions of greenhouse gases have caused rapid global warming at a rate unprecedented in at least the past 2,000 years. Rapid global warming has been accompanied by increases in the frequency and intensity of heat extremes over most land regions in the past 70 years.

While human activities cause emissions of a number of greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide (CO₂) stands out as the leading culprit. This is because of its relatively long atmospheric lifetime and because human activities cause much higher emissions of CO₂ than other greenhouse gases.

To avoid reaching unsafe global temperatures, climate scientists have concluded we can’t prevent continued global warming without reaching a state of net zero CO₂ emissions.

But how might climate extremes change after net zero CO₂? There is limited research on this. Our new study, published in Environmental Research Letters, uses a collection of models to address this gap. We found temperatures would respond very differently in various parts of the world, and heat extremes might continue to disproportionately affect vulnerable populations.

The greenhouse effect and net zero emissions

The world’s land and oceans have taken up most of the carbon humanity has emitted over the past six decades. However, land and oceans are incapable of absorbing 100% of CO₂ emissions.

The remaining CO₂ emissions over the past 60 years have been absorbed by the atmosphere, leading to an enhanced greenhouse effect. This has caused the especially rapid warming we’ve observed in the recent past.

To stop the continued enhancement of the greenhouse effect, we need to reach net zero CO₂ emissions. Achieving net zero means reaching an overall balance between the CO₂ emissions humans produce and the CO₂ humans remove from the atmosphere.

The urgency of reaching net zero CO₂ emissions has sparked the use of state-of-the-art climate modelling techniques to answer the question – how does our climate change after net zero?

What lies beyond net zero CO₂?

To try and answer this question, we used climate simulation models with increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Then, CO₂ emissions are “turned off” and simulations continue for 100 years more. This simple experimental setup allows us to compare the climate before net zero to climate patterns we might see after a transition to net zero.

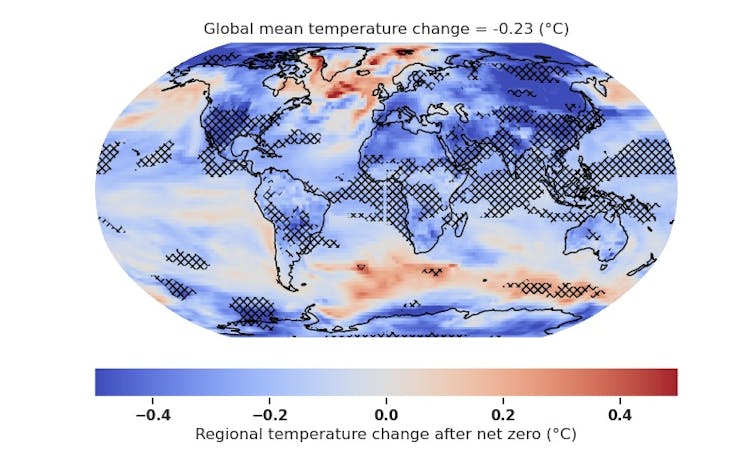

There are regions where projected climate change patterns after net zero CO₂ are very uncertain. However, we saw several strong patterns:

- land cools after net zero CO₂ is achieved, while the ocean takes a bit more time to respond with some areas cooling and others warming;

- the Southern Ocean continues to warm after net zero CO₂;

- global temperature change (-0.23°C) is not always a good representation of regional temperature changes.

Author provided

Heat extreme patterns after net zero CO₂

Currently, less economically developed regions experience disproportionate loss and damage from climate extremes. Should we expect this to persist after net zero CO₂ emissions, or will the inequality of climate change be resolved by net zero?

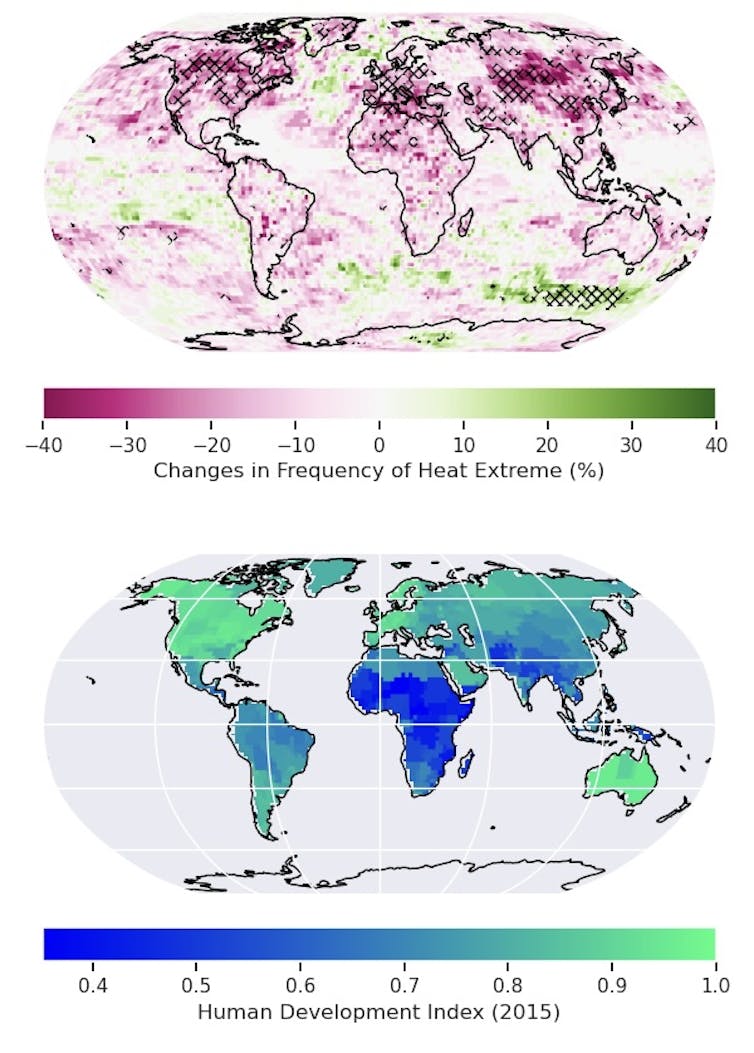

We explored this issue by investigating if there are any changes in how often local heat extremes occur 100 years after net zero compared to how often they occur before net zero.

We then compared our results to maps of the Human Development Index – a measure of socioeconomic development where regions with a high rank have higher incomes, more access to education and longer life expectancy. Other similar development indicators include the Multidimensional Poverty Index.

Although there are widespread decreases in how often heat extremes occur after net zero CO₂ emissions, regions with a relatively higher human development index such as North America and western Europe experience larger reductions in heat extremes than regions with a lower rank, such as Sub-Saharan Africa and southeast Asia.

Author provided

Preparing for a post net zero world

We need to reach and sustain net zero CO₂ emissions to halt continued global warming. Models that emulate the transition to net zero CO₂ project large-scale cooling over land, and widespread reduction in land-based heat extremes.

However, post-net zero reductions in heat extremes favour regions with a higher human development index over regions with a lower index. This means the inequality of climate change may persist even after net zero CO₂.

Our study represents a step toward understanding climate extremes after net zero CO₂ emissions are achieved. For now, it is imperative that humanity works without delay to achieve net zero emissions to avoid the most severe climate change impacts affecting future generations.![]()

Liam Cassidy, PhD Candidate, The University of Melbourne; Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne; Josephine Brown, Senior Lecturer, The University of Melbourne, and Tilo Ziehn, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

***

Authors

Liam Cassidy

PhD Candidate, The University of Melbourne

Andrew King

Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

Josephine Brown

Senior Lecturer, The University of Melbourne

Tilo Ziehn

Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO

Disclosure statement

Andrew King receives funding from the National Environmental Science Program.

Josephine Brown receives funding from the National Environmental Science Program.

Tilo Ziehn receives funding from the Australian Government under the National Environmental Science Program.

Liam Cassidy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.